“These days it might be said that I’ve never really accepted that I’ve been deeply scarred by it.” LOL

On March 1, 2025, I attended a conversation between Sir Nigel Biggar and Dr. Margaret MacMillan about the history and morality of colonialism, at an event in Toronto hosted by the Canadian Institute for Historical Education and sponsored by the National Post (complete recording). In this excerpt (1:30:56 to 1:34:50), Biggar and MacMillan respond to a question from the audience about whether “the current cultural climate of uncritical criticsm of the past” reflects “active malice.” MacMillan takes the opportunity to mock the notion of historical collective (intergenerational) trauma. Widespread laughter from the audience spurs Biggar oto add his own “frivolous comment” about how unimpressed he’s always been with his beatings at school.

|

|

Biggar: “My perception of the situation is that the dogmatic zealotry – shall we call it “malice” – of a minority rides on the back of the ignorance and uncertainty of the majority. I mean, most people know nothing about, in your country or mine, know nothing about colonial history, except what they read in the newspapers or read on social media. So there’s a vast – can you have a vast pool of ignorance? – I guess you can, which means that, when some people come along, who are absolutely certain of the truth and will punish you, if you try and say otherwise, a lot of people say, “Well, why would you pay a cost for that?” So, I think that’s what’s going on. But, my sense is, more and more people are realising that there are a lot of social costs to letting false narratives prevail. And more and more people are getting fed up with being told what to think. Which is why this meeting, which is why the Canadian Institute for Historical Education came into being. It’s why the Free Speech Union [of Canada] was launched last night. It’s why this meeting is held. So, I’m hopeful, in time, that there’ll be a proper corrective, back into something more balanced.

MacMillan: I think also we have – and this may be tied with societal changes – we have a culture which is very much aware of hurt and damage that can be done to people. And so we talk about trauma as something that can be passed down through generations. And I think that also adds to the way in which we examine the past, that dreadful things happened in the past and they are still rippling through our societies. In some cases, that is true. I myself am a bit sceptical that trauma can be passed down somehow in a genetic makeup. You know, when I think of, my great grandfather was beaten at school in Wales for speaking Welsh. I’ve read about it. It doesn’t affect me. It hasn’t affected my life. It hasn’t affected, didn’t affect my mother’s life. It didn’t affect my grandmother’s life. These days it might be said that I’ve never really accepted that I’ve been deeply scarred by it. [Laughter] But, anyway. But it, there is, you know, different currents often come together in societies. And I think the whole culture of therapy, which is, was essential and necessary in many ways and has done a lot of good, perhaps also tends to make everything in the past into a trauma, which leaves these grievous scars.

Biggar: Well, I’ll make the frivolous comment that I was caned at school, so I got real scars. But did it leave a lasting impression? Not at all. It was very effective in stopping me talking in the dormitory. [Laughter] That’s frivolous. But I guess I’m of a certain age and I just noticed the collapsing of what I used to think of as distress, and everything is trauma. Anything that’s distressing is trauma. For me, trauma is what’s happening to Ukrainians on the front line. Which is not to say, that there may not be forms of distress that are very serious. But, in the same way, my friend there, in terms of applying the word “atrocity” to the kind of injustice you described, I want to say, “No, I want to reserve that word for something rather more grave than that, serious as that might be”. So, with trauma, I want to be more precise. I reserve that for really serious things [my transcription].”

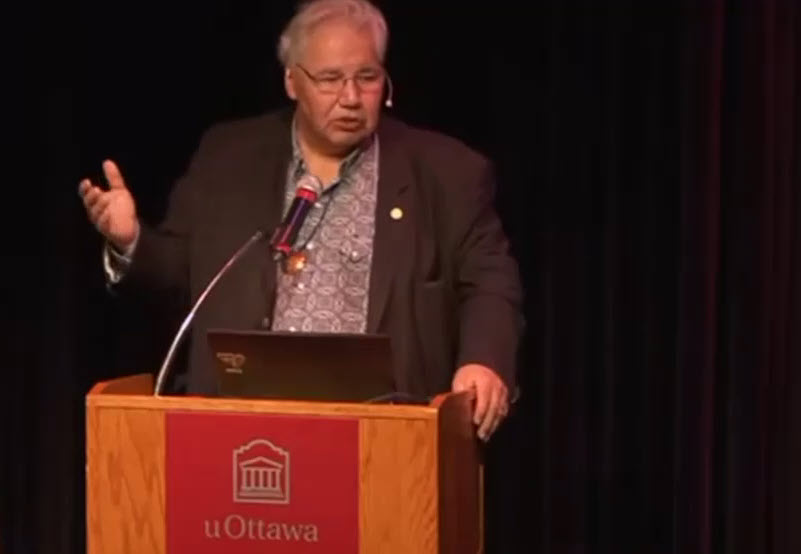

In contrast to this woefully ignorant, egocentric, and self-satisfied display, the Honourable Justice Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRCC), spoke gravely about the legacy of Indian Residential Schools to the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences in Ottawa, Ontario, on May 30, 2015 (complete recording). In this excerpt (29:12 to 30:31), Sinclair relates the severity of impact of Indian Residential Schools to their operation over multiple generations.

|

“Residential schools were with us from the early 1880s, late 1870s, until 1996, when the last residential school closed in Canada. So, they were around for about 125 years. If you think about that, that’s about seven generations of children, who went through the schools. And I’ve pointed out – and, I think, it’s probably true – those of you, who are experts in the field, can give me your thoughts later, if you wish – but, if the schools had only been in place for one or two generations, they wouldn’t have had the impact that we’re now seeing, because the children would have been able to go back home, and they would have had adults and others in their lives, who would have been able to help them to heal from that experience. There would have been culturally strong people and leaders in the community, that would have helped them recover from this, if the schools had only been in place for 10 or 20 years or 30 years, maybe. But the schools were in place for 125 years. So, that eventually, by the time children were going back to their communities, they were going back to their communities filled with residential school survivors, who themselves had been throught the school system, and who themselves had suffered as a result of being in the schools [my transcription].”

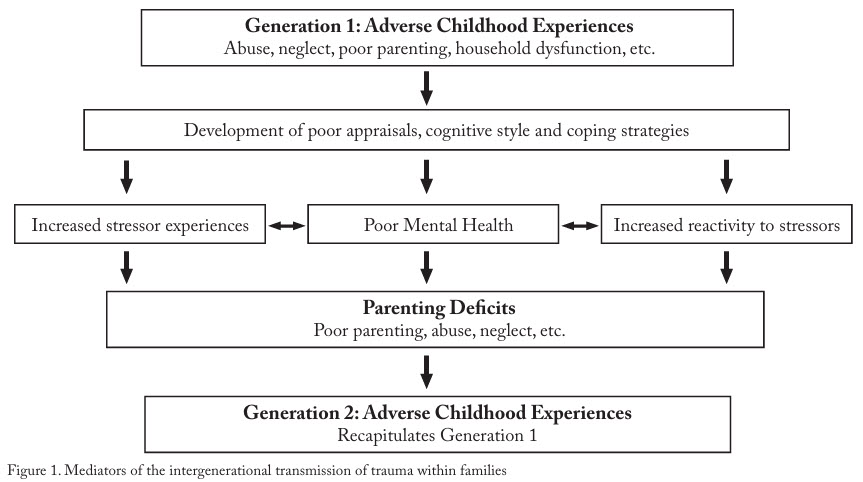

To learn more about historical collective (intergenerational) trauma, I can do no better than to recommend the work of Dr. Amy Bombay, an Anishinaabe researcher at Dalhousie and Carleton Universities, whose family has been affected by the residential school system and the child welfare system. Dr. Bombay has spent a career studying Indigenous well-being and its links with settler colonialism in Canada. Figure 1 is from her 2009 paper, Intergenerational Trauma: Convergence of Multiple Processes among First-Nations peoples in Canada.

Please feel free to download a resource pack of over 40 papers, including several by Dr. Bombay, covering events, responses, and treatment relating to historical collective (intergenerational) trauma.

Licence

We are publishing this material under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. If you find use for our work, please credit Paul Allen (https://paulallen.ca).