Canada Day 2020 marks the fifth anniversary of the unveiling of a bronze statue of John A. Macdonald Holding Court (MHC) on Picton Main Street. Supporters and critics of MHC disagree strongly about Macdonald’s legacy and what honouring him with public memorials says about us. After learning that there’s no evidence for the truth of the main event depicted in MHC, I hope that some of its supporters will share in a reconsideration of the statue’s place in our community.

Signing a petition to “Remove the John A. Macdonald Monument ‘Holding Court’ from Main Street Picton, Ontario” would be a good start.

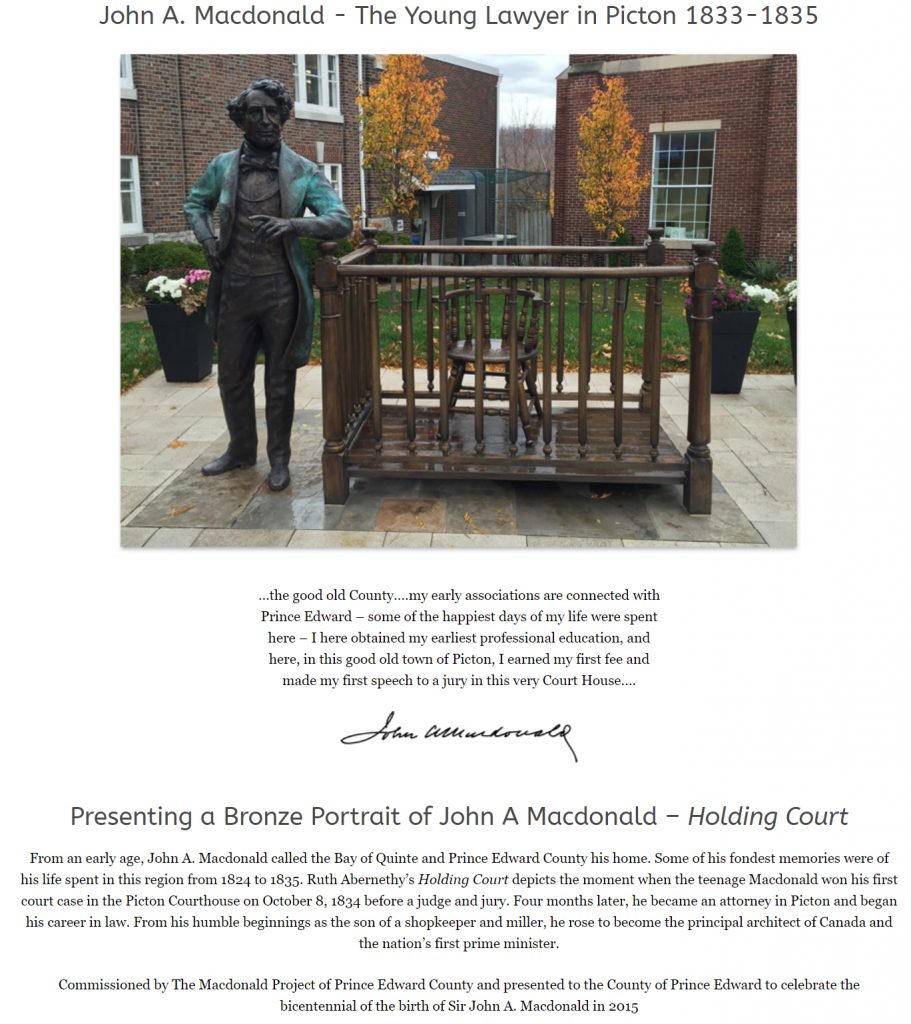

The Macdonald Project homepage includes a photo of MHC, an excerpt of remarks attributed to Macdonald, and its sponsor’s central claim about the statue’s historical significance:

When The Macdonald Project began to promote and fund-raise for MHC in 2010, Macdonald was a largely uncontroversial – and even unrecognizable – historical figure. An Ipsos-Reid survey in June 2009 found that three-in-five Canadians were unable to identify Macdonald from his picture.

Five years on, when it was time to unveil MHC, Macdonald was better known, due partly to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s revelations that Macdonald had designed and waged a campaign of cultural genocide against First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples, beginning shortly after Confederation and continuing ‘til his death in 1891.

Despite these shattering revelations, Municipal Council of Prince Edward County insisted on installing MHC in front of The Armoury on Picton Main Street on Canada Day 2015.

In the intervening years, public memorials to Macdonald have generated heated debate – and even political protest – across Canada, including in Kingston, Montreal, Toronto, and Victoria. MHC in Picton is no exception.

Early in 2019, the County had removed MHC from public view, while The Armoury’s owners improved their property. On May 16, 2019, Council agreed to relocate MHC eventually to the forecourt of the Public Library, adjacent to The Armoury. Likely in anticipation of public criticism of its plan, Council announced a series of talks that I’ve heard Councillor Kate McNaughton describe variously as “contextualizing” the statue, “decolonizing” the land it occupies, and “continuing the hard work of Reconciliation.”

The inaugural talk, entitled The Memorialization of Sir John A. Macdonald, was given on November 12, 2019, by Dr. Niigan Sinclair, the son of Senator Murray Sinclair, former Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Dr. Sinclair’s talk inspired me and other citizens to ask Council to postpone the re-installation of MHC on Picton Main Street until Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents of the County had been consulted. Readers can review a video-recording and transcript of the deputation, comments, and Q & A.

Despite Dr. Sinclair’s recommendation and our request for public consultation, Council insisted on re-installing MHC in front of the Public Library around noon on December 23, 2019.

Within minutes, The Picton Gazette was announcing “County to consult public on Sir John A. Macdonald statue.” Mayor Ferguson was quoted as wanting to “hear ideas about ways we can recognize our first Prime Minister’s complex legacy [and] help our community think more deeply about the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples.”

A television interview with an early supporter of MHC was soon added to the Council’s messaging. This public personality repeated the familiar, but unfounded claim that “[Macdonald] had his very first court case here in October of 1834 and that’s what this statue actually represents: his first court case, which is very historic [my emphasis].”

Lots has happened since Council insisted on re-installing MHC on Picton Main Street in December 2019: nation-wide protests in support of the Wet’suwet’en people; a global pandemic and ensuing financial crisis; and international protests of police violence and other racist acts against Black people. Anti-racism protests have targeted public memorials that honour notorious figures, including statutes of a slave-trader in the UK, Confederate traitors in the US, and John A. Macdonald in Canada.

Trying to emerge from these challenging times, the Municipal Council of Prince Edward County has announced “public consultation with regard to reworking public spaces.” This consultation is a good opportunity to reconsider MHC’s place in our community.

I’d like to make a small contribution to this consultation. Anyone who’s worried that removing MHC from Picton Main Street would amount to erasing an important part of local history can relax:

There’s no evidence that the main event depicted in Macdonald Holding Court ever happened.

You might wonder, “How can this be true?“

The Macdonald Project identifies a handful of primary sources for MHC:

- court records of Dr. Thomas Moore’s and John A. Macdonald’s trials in Picton in 1834

- a newspaper account of Macdonald referring to his first case in Picton, published c. 1861

- one anecdote describing an altercation between Macdonald and Dr. Moore, published in 1895

- two anecdotes describing Macdonald’s first case in Picton, published in 1895 and 1905

Let’s consider the relevance and reliability of each of these primary sources in turn.

The King vs John A McDonald [sic]

Court records confirm Dr. Thomas Moore’s conviction and John A. Macdonald’s acquittal on charges of assaulting each other at the General Court of Quarter Sessions of the Peace held in Picton on October 8, 1834.

A personal note: My father’s family settled in the Newcastle District in 1825 and I’ve researched archival materials from this period for over thirty years. Based on my experience, it’s remarkable that these court records have survived. So that readers might enjoy and evaluate these historical documents for themselves, I’ve included facsimiles and transcriptions in the Exhibits below.

The court records identify three different roles that Macdonald played that day: victim and witness in Dr. Moore’s trial and defendant in his own. For all the fascination that they might hold for us, the court records provide no evidence that Macdonald ever played the role of lawyer-defending-himself.

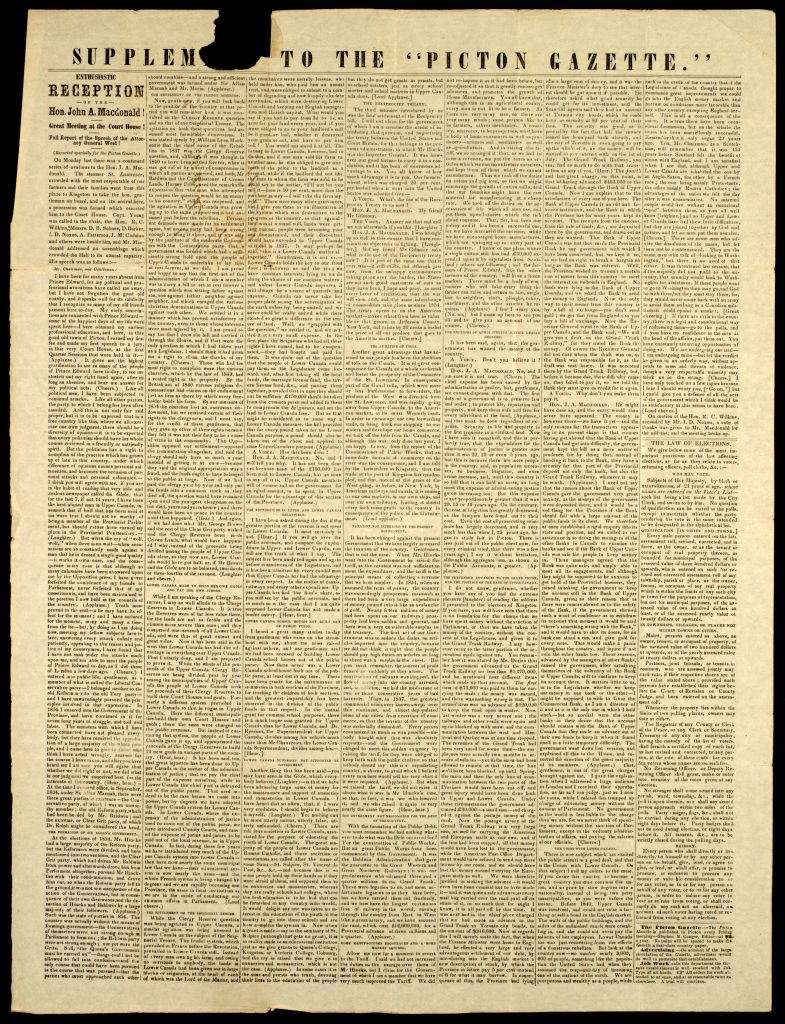

The Picton Gazette’s account of Macdonald referring to his first case in Picton

The Macdonald Project homepage includes an excerpt of remarks attributed to Macdonald regarding his first case in Picton. Again, so that readers might evaluate this historical document for themselves, I’ve included a facsimile of the original Supplement to The Picton Gazette (c. 1861) in the Exhibits below. Here’s the unedited version of Macdonald’s opening remarks to a gathering of friends outside the Picton Court House:

Mr. Chairman, and Gentlemen:

I have been for many years absent from Prince Edward, for my political and professional avocations have called me away, but I have not forgotten the good old county, and it speaks well for its salubrity that I recognize so many of my old friends present to-day. My early associations are connected with Prince Edward – some of the happiest days of my life were spent here – I here obtained my earliest professional education, and here, in this good old town of Picton, I earned my first fee and made my first speech to a jury, in this very Court House, at the first Quarter Sessions that were held in it. (Applause.)

Now, the main event depicted in MHC would be the perfect segue way, as Macdonald shifted from his opening to complaining about the calumny that beset him every day:

Like all political men, I have been subjected to continual attacks…. I think you will agree with me, if you are in the habit of reading that very able and zealous newspaper called the Globe, that for the last 7, if not 14 years, I have been the best abused man in Upper Canada, insomuch that if half that has been said of me were true I should not be worthy of being a member of the Provincial Parliament, but should rather have earned my place in the Provincial Penitentiary. – (Laughter.)

And yet, in regaling his friends with the story of his first case in Picton, Macdonald never mentions that, in this very case, he’d defended himself successfully against a false charge of assaulting a person, who was the truly guilty party. Whatever one makes of The Picton Gazette’s account of Macdonald’s speech that day, it clearly provides no evidence for the main event depicted in MHC.

“Entertaining Anecdotes” about Macdonald

According to The Macdonald Project‘s website, all of the remaining sources for the main event depicted in MHC are unreliable exaggerations, originating with Macdonald himself:

There are at least five versions of [Macdonald’s] practical joke on Dr. Thomas Moore. Most accounts of the incident and trial are versions of the entertaining anecdotes taken from the Macdonald biographies by E. B. Biggar (1891), or Sir Joseph Pope (1915). Both were written decades after the incident and both rely on John A. Macdonald’s own story telling for their entertainment value – not a reliable source of information. John A. was known for exaggerating his stories during dinner parties or political speeches [my emphasis].

We can easily show that these “entertaining anecdotes” also provide no evidence for the main event depicted in MHC.

Biggar’s account of an altercation between Macdonald and Moore

E. B. Biggar’s Anecdotal Life of Sir John Macdonald (1891) includes an anecdote describing an altercation between Macdonald and (apparently) Dr. Moore, at an Orange Day Parade in Picton, on July 12, 1834:

A friend who knew [Macdonald] well here gives this reminiscence of his Picton life: “When he was reading law in Picton, he used to get into some funny scrapes, but always had friends to help him through. There was a certain Dr. ___ here, who was a strong Reformer at that time, and as the Orangemen were mostly Conservatives, this doctor did not like them, I suppose more on that account than from being Orangemen. One Twelfth of July they walked in Picton, and the doctor came rushing up town, saying: ‘What a shame it is for those ruffians to come in to destroy the peace of the town. There will be bloodshed.’ John A., with several young gentlemen, were standing in front of the Hopkins House, when he slipped behind the doctor, and pinned a long Orange ribbon to his coat. When the doctorfound it out he was very angry. The gentlemen that were with John A. told him he had better see the doctor and apologize, as he was an elderly gentleman. John A. did so; but in the afternoon the doctor, coming up the street, again saw the same parties in the same place laughing, and supposed they were laughing at him. The doctor, stopping, said: “Some puppy pinned an Orange ribbon to my coat this morning. He was not an Irishman, nor an Englishman, but a lousy Scotchman.” John replied, ‘Doctor, I apologized, and said I was sorry for what I did, but you must not speak in that way of my nationality, for I will not put up with it.’ The doctor answered, ‘Shut up, you puppy, or I will box your ears.’ John A. replied, ‘You are not able.’ The doctor kicked at him, but John A. caught his foot, threw him down, and was hammering away (to the delight of the by-standers) when a magistrate appeared on the scene, commanding peace in the King’s name, and telling the crowd to stand back. The magistrate pulled John A. off the doctor, but as he did so he whispered, ‘Hit him again, Johnnie!” [pp. 32 – 33].

That’s it. No mention of Macdonald defending himself. No mention even of charges being laid. Clearly, no evidence for the main event depicted in MHC.

Biggar’s account of Macdonald’s first case in Picton

Biggar’s biography does include another anecdote that purportedly describes Macdonald’s first case in Picton – but this case obviously has nothing to do with the main event depicted in MHC:

[Macdonald’s] first case was one in which his client sued the magistrate on some trifling ground, and he often afterwards told with great gusto of the magistrate’s indignation at being thus bearded in his den, and the amusement the suit gave rise to. [p. 31]

Pope’s account of Macdonald’s first case in Picton

The Macdonald Project’s last remaining source for the main event depicted in MHC is yet another (and very different) account of Macdonald’s first case in Picton. This “amusing anecdote” appeared in J. Pope’s The day of Sir John Macdonald – A chronicle of the first Prime Minister of the Dominion (1915):

In Macdonald’s first case, which was at Picton, he and the opposing counsel became involved in an argument, which, waxing hotter and hotter, culminated in blows. They closed and fought in open court, to the scandal of the judge, who immediately instructed the crier to enforce order. This crier was an old man, personally much attached to Macdonald, in whom he took a lively interest. In pursuance of his duty, however, he was compelled to interfere. Moving towards the combatants, and circling round them, he shouted in stentorian tones, ‘Order in the court, order in the court!’ adding in a low, but intensely sympathetic voice as he passed near his protege, ‘Hit him, John!’ I have heard Sir John Macdonald’s say that, in many a parliamentary encounter of after years, he has seemed to hear above the excitement of the occasion, the voice of the old crier whispering in his ear the words of encouragement, ‘Hit him, John!’ [pp. 8 – 9]

This scene would undoubtedly make for an attention-grabbing statue on Picton Main Street (maybe called Choke-Holding Court), but there’s no evidence that Macdonald was defending himself (as a lawyer, at least) in this mêlée.

With this, The Macdonald Project has run out of primary sources for us to consider; none provides evidence for the main event depicted in Macdonald Holding Court.

Supporters and critics of MHC disagree strongly about Macdonald’s legacy and what honouring him with public memorials says about us.

Some supporters of MHC have argued that “All history matters.” They might permit critics “to add to” but never “to take from” what they call “history” – as though stitching a clean patch on one’s pocket might somehow undo a dark stain on one’s sleeve. No matter Macdonald’s bad deeds, and no matter this idol’s misrepresentations, these supporters will insist on Macdonald Holding Court forever on Picton Main Street.

For other supporters of MHC, historical truth matters and the statue’s purported authenticity is a crucial consideration. Our demonstration that there’s no evidence for the main event depicted in Macdonald Holding Court may persuade these supporters to share in a reconsideration of the statue’s place in our community.

Signing a petition to “Remove the John A. Macdonald Monument ‘Holding Court’ from Main Street Picton, Ontario” would be a good start.

Exhibits

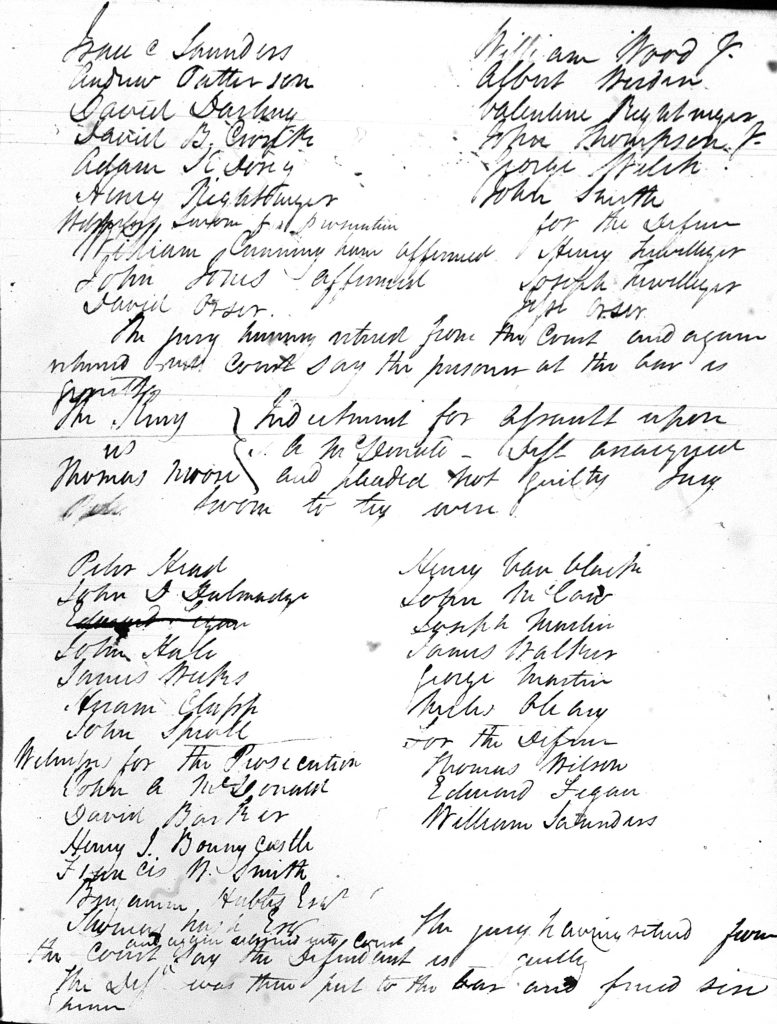

Facsimile of Court Record of Dr. Thomas Moore’s Trial

Transcription of Court Record of Dr. Thomas Moore’s Trial

| . . . | . . . |

| The King vs Thomas Moore | Indictment for assault upon J.A. McDonald [sic]. Def[endan]t arraigned and pleaded not guilty. Jury sworn to try were: |

| Peter Head John D. Dulmadge John Hale James Weeks Hiram Clapp John Sprall | Henry Van Vlack John McCan Joseph Martin James Walker George Martin Miles O’Leary |

| Witnesses for the defense: Thomas Wilson Edward Fegan William Saunders Witnesses for the prosecution: John A. McDonald David Barker Henry J. Bonnycastle Francis N. Smith Benjamin Hubbs, Esq. Thomas Nash, Esq. | |

| The Jury having retired from the Court and again returned into Court say the Defendant is guilty. The Def[endan]t was then put to the bar and fined six pence. |

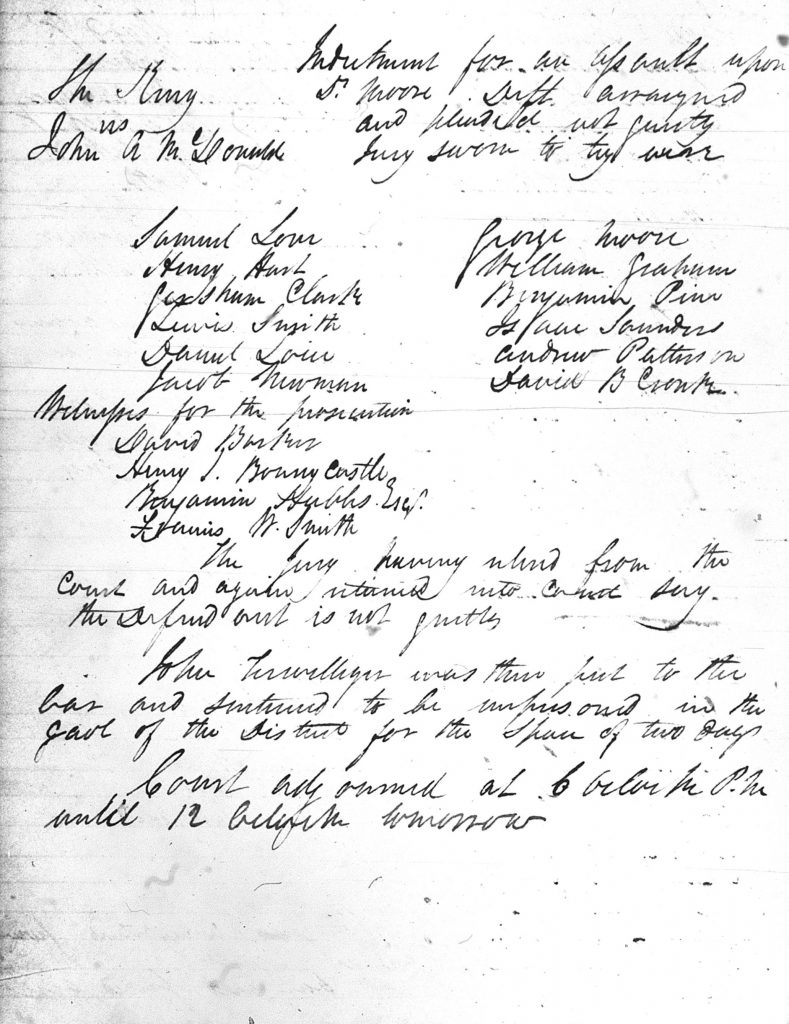

Facsimile of Court Record of John A. Macdonald’s Trial

Transcription of Court Record of John A. Macdonald’s Trial

| The King vs John A McDonald [sic] | Indictment for an assault upon Dr. Moore. Def[endan]t arraigned and pleaded not guilty. Jury sworn to try were: |

| Samuel Low Henry Hart Gresham Clark Lewis Smith Daniel Low Jacob Newman | George Moore William Graham Benjamin Pine Isaac Saunders Andrew Patterson David B. Cronk |

| Witnesses for the prosecution: David Barker Henry J. Bonnycastle Benjamin Hubbs, Esq. Francis W. Smith | |

| The Jury having retired from the Court and again returned into Court say the Defendant is not guilty. | |

| . . . | |

| Court adjourned at 6 o’clock PM until 12 o’clock tomorrow. |

Facsimile of Supplement to The Picton Gazette, c. 1861